ANWYN

HOWARTH

Cultivars of the Digital Kind

Studio Technogeographies

27–07–2023

The process of digitisation, that is the archiving, mapping and replicating of geographical spaces in the digital realm is being adopted as a climate mitigation strategy for populations at risk of submersion from rising sea levels.

In an address to the UN at COP27, Tuvalu Foreign Affairs minister Simon Kofe announced plans for the island nation to move its national sovereignty and statehood to the metaverse. Working with developers and supported by Amazon Web Services, Tuvalu will become the world’s first digital nation as rising sea levels threaten to submerge the nation underwater. But what is lost in this digitisation process? And what is there to be gained for those left stateless?

A quintessential Tropical Paradise, Tuvalu seems a world away from the AWS data centres it is set to inhabit. Nevertheless, the island nation is not so far from the digital world as it would appear, as it is in the unique position to capitalise on its much sought-after domain name — .tv. By leasing its domain to service providers who then licence to companies for use in their internet addresses, Tuvalu makes an estimated $12 million a year (almost 20% of its annual GDP) thanks to increased demand for use of .tv amid the online video streaming boom on platforms like Twitch and Vice.

The .tv economy will continue to generate revenue long after Tuvalu ceases to exist physically, however the remaining 80% of its economy relies heavily on its ancient agricultural industries, most importantly, its abundant supply of coconuts.

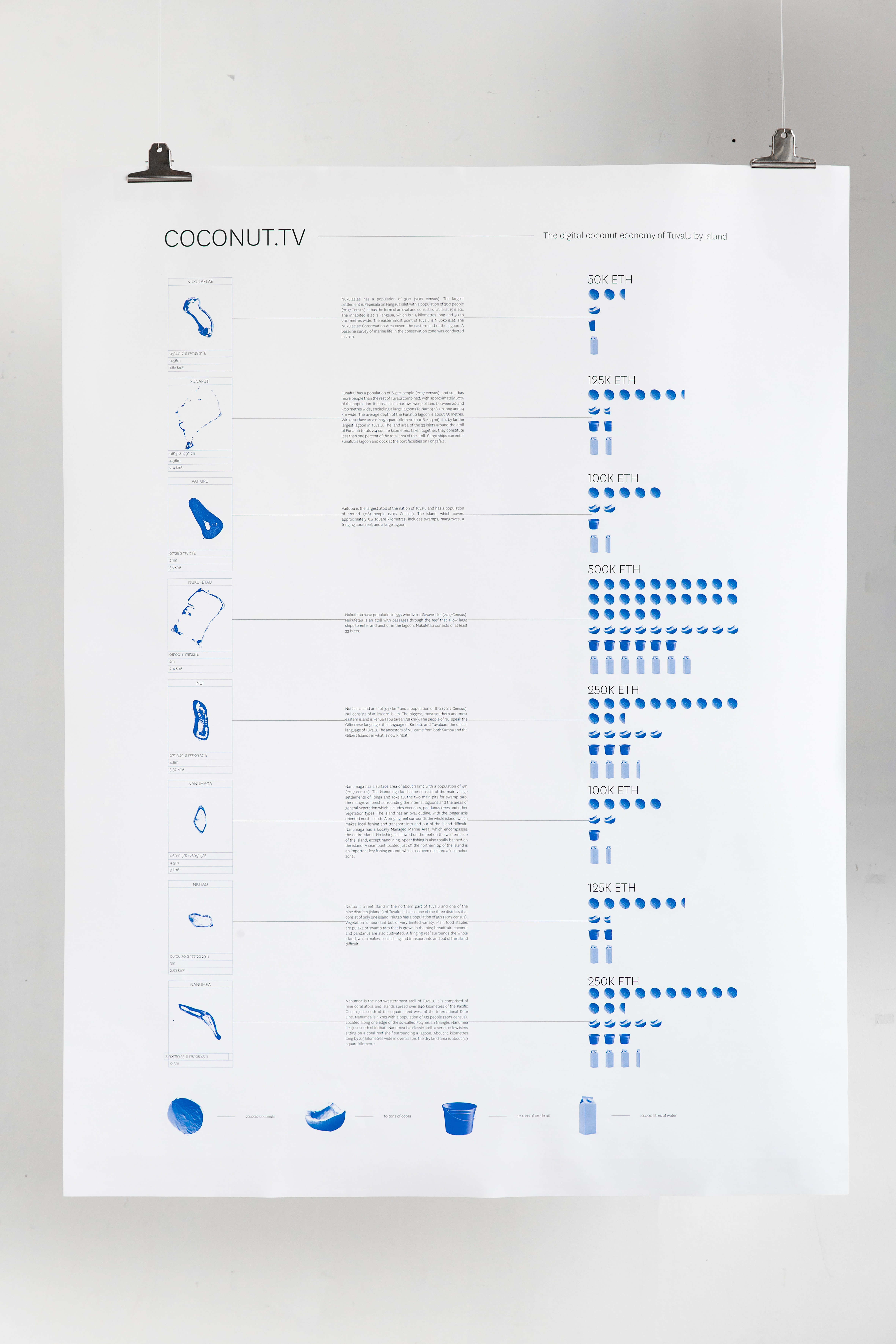

In a speculative scenario in which I am invited as a collaborator to archive and digitise Tuvalu’s coconut industry, certain considerations arise. How might the coconut industry on Tuvalu continue production in digital form, where coconuts can be traded as poly component tokens that scale in value with projections of real-time agricultural factors? What might a digital economy look like that brings value to future generations of the indigenous population? And how could the adverse effects of climate change be put to the advantage of those most at risk?

In an address to the UN at COP27, Tuvalu Foreign Affairs minister Simon Kofe announced plans for the island nation to move its national sovereignty and statehood to the metaverse. Working with developers and supported by Amazon Web Services, Tuvalu will become the world’s first digital nation as rising sea levels threaten to submerge the nation underwater. But what is lost in this digitisation process? And what is there to be gained for those left stateless?

A quintessential Tropical Paradise, Tuvalu seems a world away from the AWS data centres it is set to inhabit. Nevertheless, the island nation is not so far from the digital world as it would appear, as it is in the unique position to capitalise on its much sought-after domain name — .tv. By leasing its domain to service providers who then licence to companies for use in their internet addresses, Tuvalu makes an estimated $12 million a year (almost 20% of its annual GDP) thanks to increased demand for use of .tv amid the online video streaming boom on platforms like Twitch and Vice.

The .tv economy will continue to generate revenue long after Tuvalu ceases to exist physically, however the remaining 80% of its economy relies heavily on its ancient agricultural industries, most importantly, its abundant supply of coconuts.

In a speculative scenario in which I am invited as a collaborator to archive and digitise Tuvalu’s coconut industry, certain considerations arise. How might the coconut industry on Tuvalu continue production in digital form, where coconuts can be traded as poly component tokens that scale in value with projections of real-time agricultural factors? What might a digital economy look like that brings value to future generations of the indigenous population? And how could the adverse effects of climate change be put to the advantage of those most at risk?