ANWYN

HOWARTH

Cultivars of the Digital Kind

Studio Technogeographies

27–07–2023

The process of digitisation, that is the archiving, mapping and replicating of geographical spaces in the digital realm is being adopted as a climate mitigation strategy for populations at risk of submersion from rising sea levels.

In an address to the UN at COP27, Tuvalu Foreign Affairs minister Simon Kofe announced plans for the island nation to move its national sovereignty and statehood to the metaverse. Working with developers and supported by Amazon Web Services, Tuvalu will become the world’s first digital nation as rising sea levels threaten to submerge the nation underwater. But what is lost in this digitisation process? And what is there to be gained for those left stateless?

A quintessential Tropical Paradise, Tuvalu seems a world away from the AWS data centres it is set to inhabit. Nevertheless, the island nation is not so far from the digital world as it would appear, as it is in the unique position to capitalise on its much sought-after domain name — .tv. By leasing its domain to service providers who then licence to companies for use in their internet addresses, Tuvalu makes an estimated $12 million a year (almost 20% of its annual GDP) thanks to increased demand for use of .tv amid the online video streaming boom on platforms like Twitch and Vice.

The .tv economy will continue to generate revenue long after Tuvalu ceases to exist physically, however the remaining 80% of its economy relies heavily on its ancient agricultural industries, most importantly, its abundant supply of coconuts.

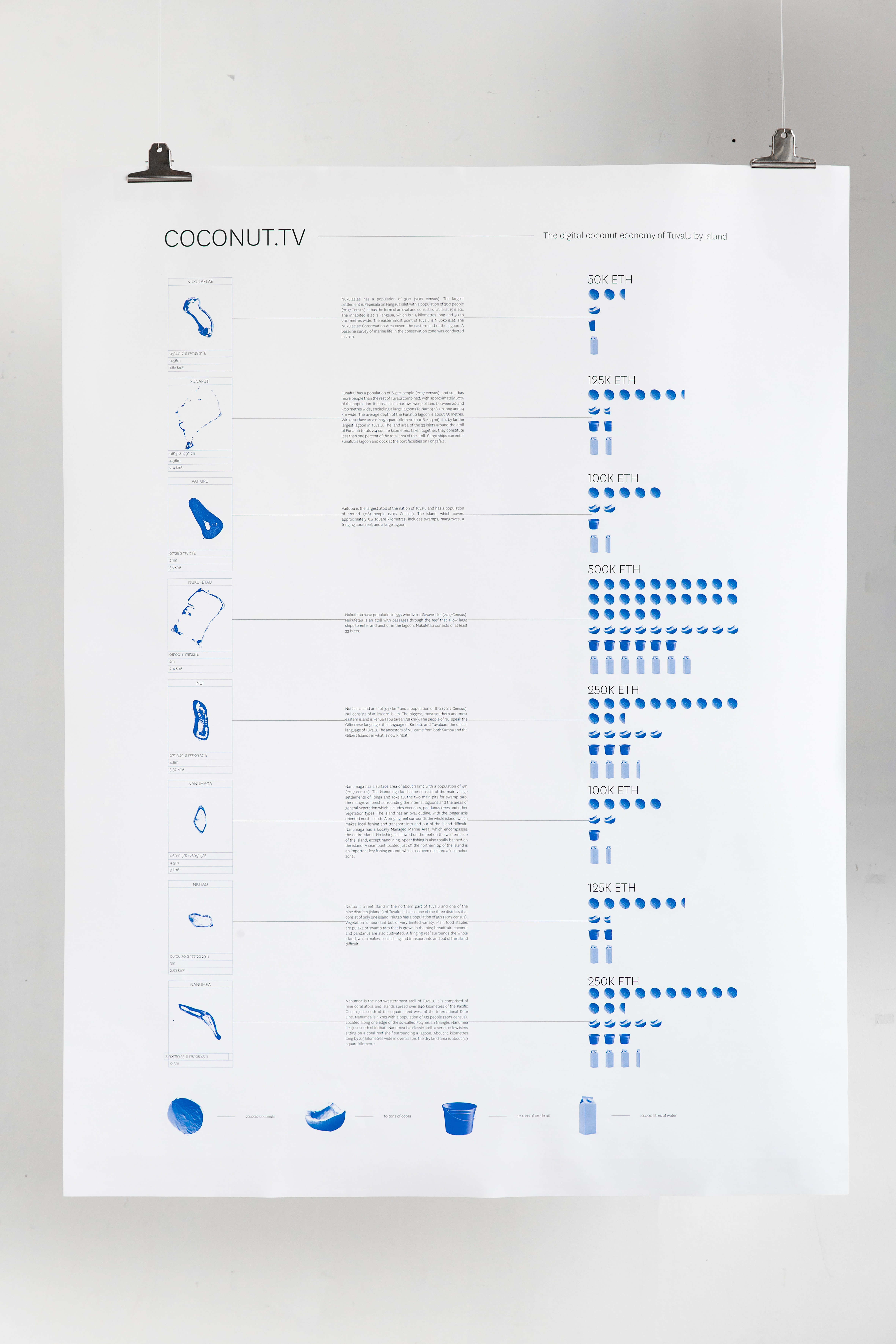

In a speculative scenario in which I am invited as a collaborator to archive and digitise Tuvalu’s coconut industry, certain considerations arise. How might the coconut industry on Tuvalu continue production in digital form, where coconuts can be traded as poly component tokens that scale in value with projections of real-time agricultural factors? What might a digital economy look like that brings value to future generations of the indigenous population? And how could the adverse effects of climate change be put to the advantage of those most at risk?

In an address to the UN at COP27, Tuvalu Foreign Affairs minister Simon Kofe announced plans for the island nation to move its national sovereignty and statehood to the metaverse. Working with developers and supported by Amazon Web Services, Tuvalu will become the world’s first digital nation as rising sea levels threaten to submerge the nation underwater. But what is lost in this digitisation process? And what is there to be gained for those left stateless?

A quintessential Tropical Paradise, Tuvalu seems a world away from the AWS data centres it is set to inhabit. Nevertheless, the island nation is not so far from the digital world as it would appear, as it is in the unique position to capitalise on its much sought-after domain name — .tv. By leasing its domain to service providers who then licence to companies for use in their internet addresses, Tuvalu makes an estimated $12 million a year (almost 20% of its annual GDP) thanks to increased demand for use of .tv amid the online video streaming boom on platforms like Twitch and Vice.

The .tv economy will continue to generate revenue long after Tuvalu ceases to exist physically, however the remaining 80% of its economy relies heavily on its ancient agricultural industries, most importantly, its abundant supply of coconuts.

In a speculative scenario in which I am invited as a collaborator to archive and digitise Tuvalu’s coconut industry, certain considerations arise. How might the coconut industry on Tuvalu continue production in digital form, where coconuts can be traded as poly component tokens that scale in value with projections of real-time agricultural factors? What might a digital economy look like that brings value to future generations of the indigenous population? And how could the adverse effects of climate change be put to the advantage of those most at risk?

The Amber Hunters

Technogeographies 3A

16-01-2024

Forty million years ago, Northern Europe was populated by abundant, subtropical pine forests. Major tectonic activity in the Earth’s surface during the Eocene levelled these forests, resulting in an excess production of coniferous tree resin. This resin was left to petrify on the forest floor before it was submerged during the Ice Age. The large quantities of ice melted and later collected in what is today the Baltic Sea, covering an archive of prehistoric ecology, perfectly preserved in amber.

Since the Stone Age, amber has been traded as a valuable commodity, opening the possibility for the first trade route between Northern and Southern Europe - The Amber Road. In the months of November and December, winter storms dislodge amber from the seabed, where it then washes up on the shore and is collected by amber hunters. To this day, cities adjacent to the Baltic Sea enjoy commercial prosperity. But a new kind of disruption to the seabed is changing how amber is collected.

Since the Stone Age, amber has been traded as a valuable commodity, opening the possibility for the first trade route between Northern and Southern Europe - The Amber Road. In the months of November and December, winter storms dislodge amber from the seabed, where it then washes up on the shore and is collected by amber hunters. To this day, cities adjacent to the Baltic Sea enjoy commercial prosperity. But a new kind of disruption to the seabed is changing how amber is collected.

The Baltic Sea is a major shipping route and one of the busiest, accounting for 15% of the world’s maritime traffic. As natural processes cause sand to pile across these shipping routes, dredger ships are employed to remove sand from the seabed and deposit it on increasingly popular tourist beaches.

Communities of amber hunters are tracking these dredging activities, locating sites along the coast where silt is deposited by night through pipes. Amber is photo luminescent, meaning it fluoresces yellow under ultraviolet light and is more easily spotted in the dark. Access to the necessary black light headsets is covert and requires insider connections, as this form of amber extraction is not yet regulated and falls in the grey area of what is considered legal by the International Amber Association.

Communities of amber hunters are tracking these dredging activities, locating sites along the coast where silt is deposited by night through pipes. Amber is photo luminescent, meaning it fluoresces yellow under ultraviolet light and is more easily spotted in the dark. Access to the necessary black light headsets is covert and requires insider connections, as this form of amber extraction is not yet regulated and falls in the grey area of what is considered legal by the International Amber Association.

At the Amber Museum in Gdansk, the evolving symbiosis between sea dredgers and amber hunters remains undocumented, raising questions about the responsibility of institutions in mediating ecological knowledge amid legal ambiguity.

Along the Bega River, habitants have taken initiative to make use of public or ‘non-space’. During our tour, I used my phone as a stencil to recreate the 16:9 ratio of the window frames on board the boat, sketching these private interventions as they appeared. Back in the studio, I paired the sketches with a scale model of the cabin wall, playing with the visual parallels of the window frames and the device I used to document them - my phone.

The outcome was a kind of mixed media interface that allows the viewer to install their own findings into the map. In this way the project becomes a subtle critique on the site researcher as primary mapper.

How might the practice of field research be better geared towards the population specific to the site? Could a personal digital device be a kind of ‘carrier bag’ for deep mapping and collective research by the very population to whom the mapping is most relevant?

The outcome was a kind of mixed media interface that allows the viewer to install their own findings into the map. In this way the project becomes a subtle critique on the site researcher as primary mapper.

How might the practice of field research be better geared towards the population specific to the site? Could a personal digital device be a kind of ‘carrier bag’ for deep mapping and collective research by the very population to whom the mapping is most relevant?